13 September 2009

I should leave Lev Grossman’s recent article in the Wall Street Journal, “Good Novels Don’t Have to Be Hard,” alone. I’ve gotten into trouble on this subject before, and I learned that my thoughts on the matter of “the difficult pleasure” vs the easy one are outdated, underdeveloped, and poorly expressed.

But apparently I have a couple of things to attempt to say in response:

First, Grossman equates the “difficult pleasures” argument with an aversion to, specifically, plot. This is simply inaccurate. I am currently reading, for instance, the highly-plotted 2666, by Roberto Bolano and could name many examples of literary novels which are well-written, challenge the reader’s mind and soul, and also evolve around, as Grossman puts it, “crisp, dynamic, exciting” plots.

The crux of this debate has never been about storytelling or non-storytelling, but about good storytelling and bad storytelling. The foundation of literature is language, and poor use of the language to tell a good story is where my beef begins and ends. It seems to me Grossman makes the same error of argument that is made repeatedly by genre-defenders: that somehow hoity-toity literary writers have something against a great plot, whereas the real objection is to the idea that a good plot covers a multitude of writing sins (and Ms. Meyers is guilty of entirely too many). Conversely, I don’t see a lot of people defending a poetically-written pile of nothing-much; all readers crave emotional and intellectual pay-off, via the thoughtfully-crafted journeys of the characters. I just want those journeys to be told in beautiful, stunning, maybe even strange language (which is not to say fancy language) that effectively renders what John Gardner called the vivid and continuous dream. If every other description includes three adverbs and the word “sparkle”, my experience of the fictional dream is not continuous. More aptly put by William Carlos Williams: “Organize the language right.”

Second, there is a problem with the term “difficult.” What do we mean by difficulty when we are talking about literature? There is James Joyce difficult, and there is Toni Morrison difficult. There is William Vollman difficult, and there is Mary Gaitskill difficult. There is Dostoevsky difficult and there is Tolstoy difficult. There is Virginia Woolf difficult and there is Hemingway difficult. I recently had a conversation with a Danish friend, to whom I confessed having avoided Proust for a long time, for fear of the difficulty. “There’s really nothing to be afraid of,” he said. “It’s a pretty easy read.” Meaning, it’s long, but not hard. Some have said the same about Bolano.

As examples of books he considers not difficult, Grossman cites Dickens and Thackeray, in which “you pretty much always know who’s talking, and when, and what they’re talking about.” So it seems to me that “difficult” in Grossman’s literary lexicon refers to a certain density or experimentalism in language and form; something that requires a person to jump out of the register of vernacular-English and conventional time and into the register of something closer to poetry or avant-garde cinema — “typographically altered, grammatically shattered, rhetorically obscure.”

Fine, but in this case, we’re really only talking about Joyce, Vollman, maybe Pynchon and David Foster Wallace, a minority of Faulkner’s novels, Beckett, and a handful of others.

But the difficulty of writers like Morrison, Tolstoy, Hemingway, Mary Gaitskill, Denis Johnson, Marilynne Robinson, Chekhov, Annie Proulx… writers who respect the language, in every sense, whose works are not particularly “difficult” to read, strictly speaking; but whose difficulty lies in their essential visions of humanity and the ways in which the stories they tell impel us to see differently, to see better, with, as Carlyle put it, “armed eyesight” — this is a difficulty which refers to something altogether different. Something in the realm of the moral and spiritual. Their characters come to endings which are often not happy or neat, but real and true nonetheless; their stories take the reader to unfamiliar and unexpected places that show us a humanity not readily on display in commercial movies, or genre romances, or thrillers in which the good guy always wins. If Grossman is taking up the cause of “easy” in this realm — then my concern is best expressed by Vaclav Havel:

The tragedy of modern man is not that he knows less and less about the meaning of his own life, but that it bothers him less and less.

Can difficult work, by the latter definition, be entertaining? I think so. Does exhilaration — like that which I feel when reading Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son or Bolano’s Last Evenings on Earth or the stories of George Saunders or ZZ Packer or Flannery O’Connor — not constitute entertainment? The “entertainment is king” argument seems to exclude even highly-plotted sexual-tension page-turners like The Age of Innocence and The Golden Bowl these days, because, well, the sentences are just too darn long and jam-packed with all those words. How reader-unfriendly.

Mr. Grossman seems to equate meaningful with boring, and in its resemblance to a recipe for perpetual adolescence (not innocuous, in the hands of, say, future leaders in the image of the George Bush’s or Hugo Chavez’s playing power games with the lives of millions of innocents) his argument troubles me a great deal.

Next up: my thoughts on Christopher Beha’s response to Grossman’s article, from the blog at n+1.

17 May 2009

The book jacket for Long for This World is done. Galleys next month. Exciting? Wish I could say yes. It’s strange when things become “final.” In every other part of life, completion feels good. With creative work, there’s a tinge of melancholy. Post-partum?

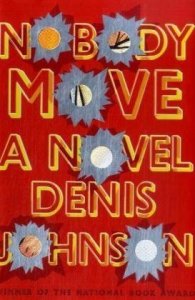

I’ve been looking at book jackets more closely lately. Anyone seen this one yet, for Denis Johnson’s new novel?

Ee-gads! There should be a disclaimer: No books were injured in the making of this book jacket. Still, can’t wait to read it.

Not Me

...

5 April 2009

I.

A student in one of my online classes writes about Don Delillo‘s “opaque” male narrators and characters, many of whom are somewhat unknown to themselves while at the same time seen in lucid flashes by the reader.

I think of Delillo often as I write Sebastian & Frederick, my first serious foray into male protagonists. Other writers who accompany me on this journey–hovering quietly–include James Salter, Hemingway, EL Doctorow, Cormac McCarthy, and Denis Johnson. The greatest difference I am sensing in writing male characters is precisely that they are less known to themselves than my female characters have been. They seem to do more than they reflect. Or it takes more action to lead them to reflection.

II.

This fall I will teach a course called “True Fiction,” focusing on writing autobiographical fiction. I am nervous about it. Initially, I pitched a class exploring the opposite — writing characters who are distinctly not ourselves, set in worlds which our far from our own. My experience with beginning writers (including myself) is that much better writing comes from the latter than the former. My college students did a first-person exercise in which they recalled a childhood memory from the perspective of a character of different gender, race, or culture. The level of writing instantly shot up a notch.

We settled on “True Fiction” because — get ready — it seemed more “marketable.” So many people are already writing fictionalized memoir, we projected we’d more likely get full enrollment. My fear is that it will turn into writing-class-as-therapy, which can produce bad, lazy writing. My intention is to assign exercises like the one my college students did (variations on their own characters, perhaps) as a way of emphasizing that one must use the imaginative muscles just as much, if not more, when writing autobiographically-based fiction.

III.

I don’t go to readings as much as I used to, partially because they started to seem very formulaic, and the writers seemed to hate being there. Invariably, the audience would try to get the writer to “admit” that the novel was really a veiled memoir. “How much of this is autobiographical?” someone would always ask. “How much of Gustave/Jill/Sammy is really you?”

The best answer I ever heard was from the novelist Chang-rae Lee who said, “All of it. And none of it.”

IV.

I’m pitching a class at a different school called “Writing Self / Writing Other.” Here’s my pitch blurb:

How do we write compelling fiction based on our lives and true experiences? And how do we write characters who are vastly different from us? In this course we will see how these two seemingly opposite approaches to fiction are in fact closely related and can fruitfully inform one another.

You’ll be the first to know if it flies.